What You Need to Know About Tax Expenditures

One of the largest parts of the federal budget – the trillions of dollars the government puts toward tax expenditures – is rarely discussed, lacks transparency, and often benefits the wealthy and well-connected above everyone else. Some tax expenditures provided through the tax code support low- and middle-income families. However, corporations and the top one percent overwhelmingly reap the benefits, and often fail to pay their fair share of taxes as a result. That should make tax expenditures an area to review as we seek to control the deficit, but while Republicans have sought to make massive cuts in most spending programs, they have to date refused to consider achieving even a dime of deficit reduction from reducing tax expenditures.

What are tax expenditures?

Tax expenditures are essentially mandatory spending programs that operate through the tax code. In its annual report, the JCT lists 216 provisions that meet the statutory definition of a tax expenditure. Like a mandatory program, the tax code sets criteria, and then whoever meets the criteria is able to receive the benefit. However, unlike traditional spending programs, instead of the federal government providing a payment of some fixed amount, the person's taxes due are reduced by that amount. In some cases, certain "refundable" tax credits can reduce tax liability below zero, and the taxpayer can get a tax refund that is more than was withheld during the year.

Tax expenditures can be structured in various ways, including:

- Deductions – subtracted from taxable income (e.g., mortgage interest deduction)

- Credits – subtracted from tax due (e.g., the earned income tax credit)

- Exclusions – income not in the tax base (e.g., employer-provided health insurance)

- Exemptions – income treated as non-taxable (e.g., municipal bond interest)

- Deferral – income earned today, but taxed in the future (e.g., 401(k) contributions)

- Preferential rates – income taxed at a special, lower rate (e.g., long-term capital gains)

Some tax expenditures are well known and widely used, such as the deduction for charitable contributions and the exclusion for employer-provided health insurance. But there are many more that few people know about and which often only benefit special interests with the best paid lobbyists.

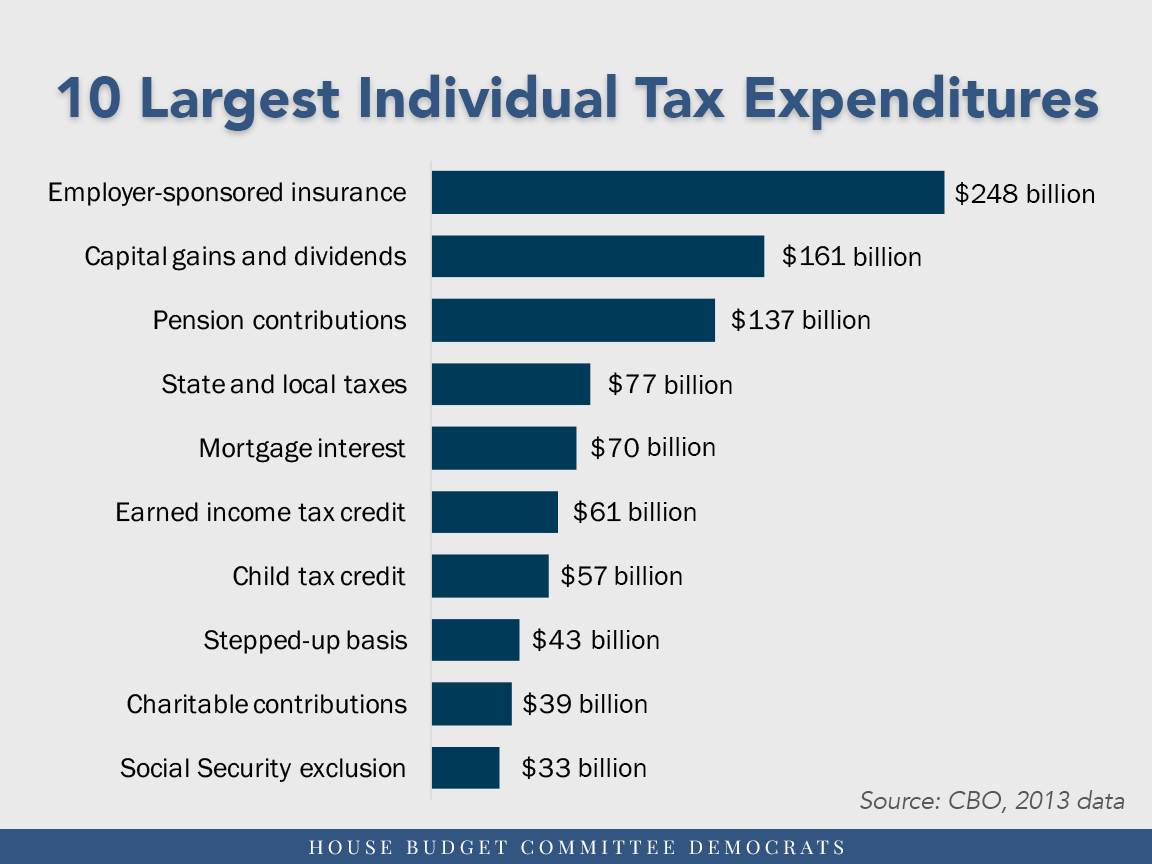

How much benefit is provided from tax expenditures?

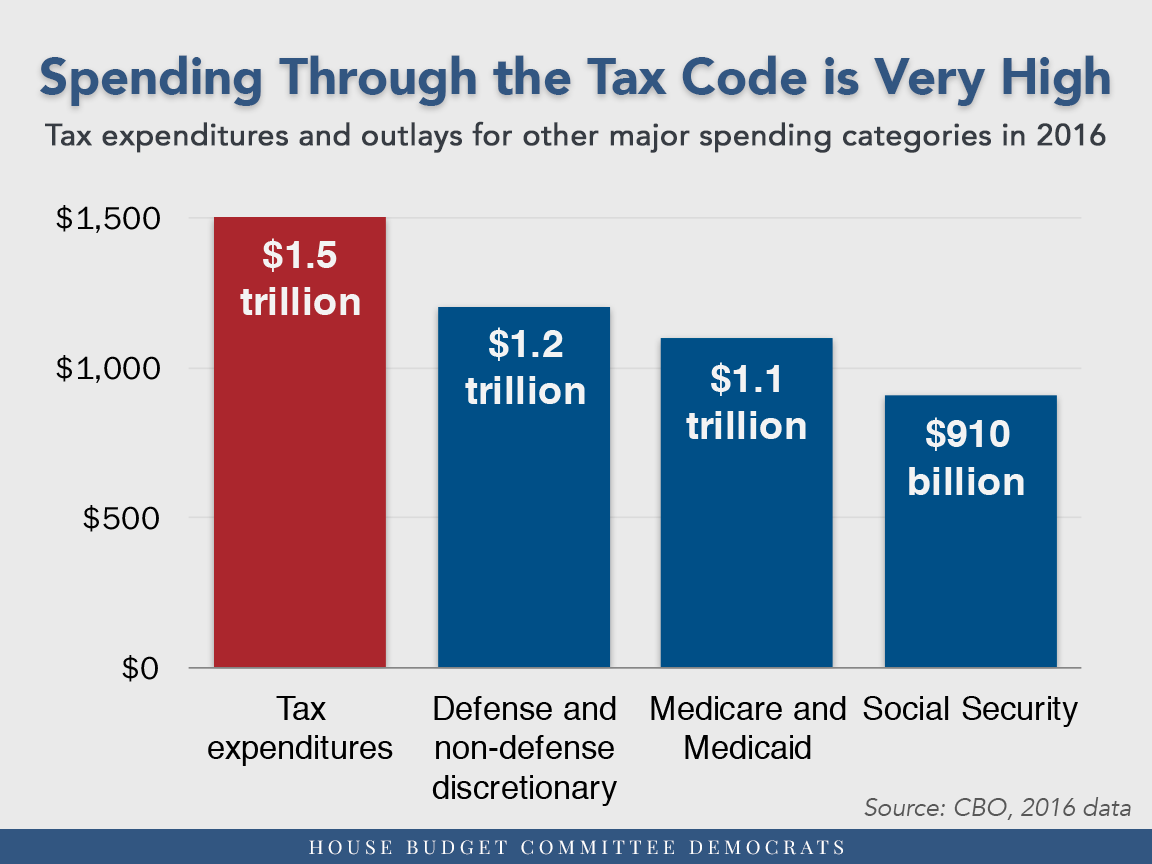

In 2016, individuals and businesses benefited from roughly $1.5 trillion in tax expenditures. This is more than was spent on Social Security ($910 billion), Medicare and Medicaid combined ($1.1 trillion), or defense and non-defense discretionary spending combined ($1.2 trillion). The total value of tax expenditures in a year is as much as the entire amount collected through the individual income tax ($1.5 trillion).

But, changing or repealing tax expenditures would not raise federal revenues by the amount of the benefit listed in the JCT's report. When tax provisions are changed, taxpayers will respond in a way that generally means less new revenue is raised than the value of the tax expenditure. Some ways that taxpayers respond include changing when to buy or sell assets, shifting income between taxable and non-taxable sources, and changing spending behaviors.

Who benefits from tax expenditures?

Many tax expenditures serve valuable purposes. For example, the earned income tax credit (EITC) provides a wage subsidy through the tax code for low-wage workers to ensure they do not get taxed into poverty. Because it is refundable, it can help workers who may owe no federal income taxes. Other tax expenditures help families afford the cost of health care, housing, education, and child care.

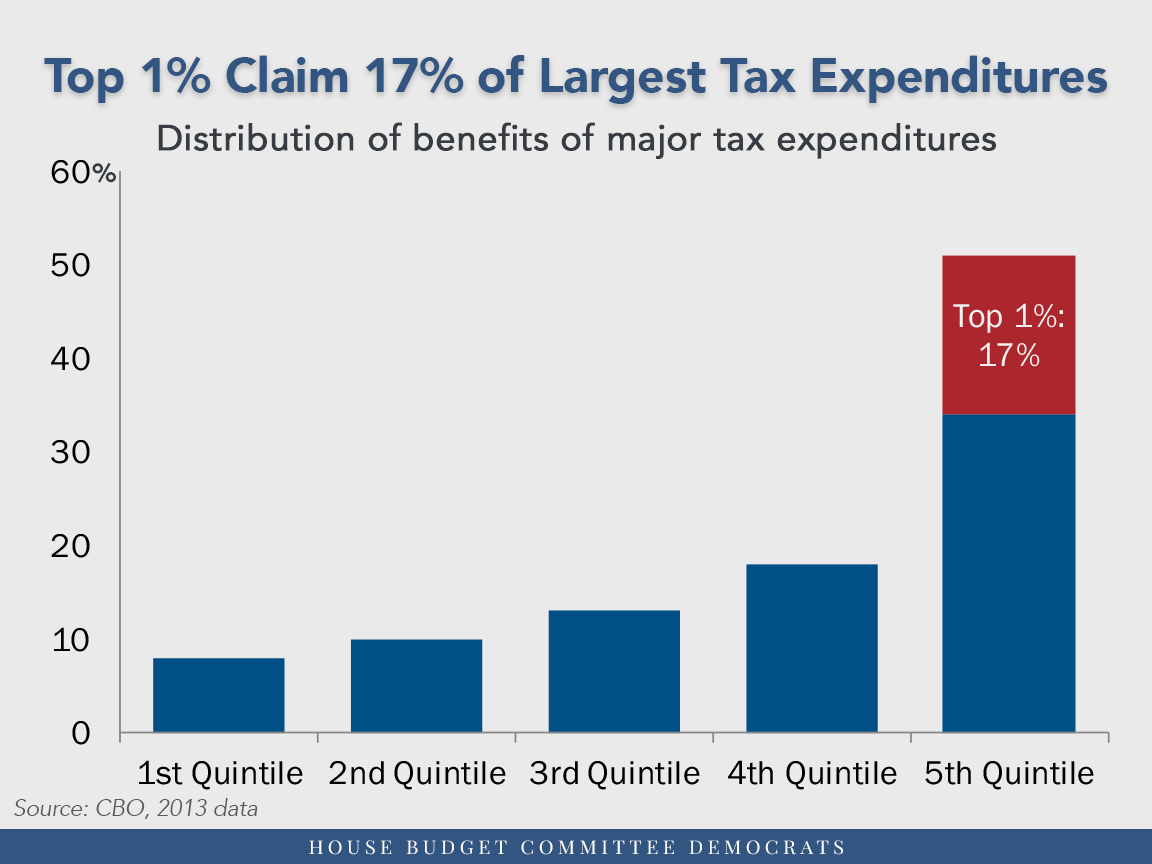

But, overall the benefits of tax expenditures are heavily weighted toward the upper end of the income scale. According to CBO, the top one percent of earners receives 17 percent of the total benefit from major individual tax expenditures, and more than 50 percent of the benefit goes to households in the top 20 percent of incomes.

There are two major factors skewing the benefit to upper-income households. First, the wealthy are much more likely to access certain tax expenditures. For example, most of the income earned from capital gains and dividends goes to upper-income households. As a result, the wealthy overwhelmingly benefit from the preferential tax rates this income receives. CBO estimates that 68 percent of the benefit from these lower rates go to just the top one percent of households. And this is one of the largest tax expenditures in the tax code – the JCT estimates it will cut taxes by $677 billion between 2016 and 2020, largely benefitting the wealthy.

Second, tax deductions provide an "upside-down benefit" – the more income you receive, the more valuable a deduction becomes. The benefit is equal to the amount of the deduction times the taxpayer's marginal tax rate. If a taxpayer has a $1,000 mortgage interest deduction and is in the highest ordinary income tax bracket (39.6 percent), the deduction provides a benefit of $396. But for a taxpayer in the lowest bracket (10 percent), the same $1,000 deduction only provides a benefit of $100. And for the majority of low- and middle-income households that only use the standard deduction, they get no benefit at all.

In addition to tax expenditures doing more for the top one percent than anybody else, many tax expenditures favor special interests with the best-connected lobbyists. Examples of these provisions include special depreciation schedules for corporate jets, loopholes that allow inversions and encourage firms to ship jobs and capital overseas, tax subsidies for the big oil companies, and corporate deductions for CEO bonuses and excessive executive compensation.

How are tax expenditures reviewed in the Congressional budget process?

The Congressional Budget Act requires that the committee report accompanying the budget resolution include estimated levels of major items and functional categories for the President's budget and in the resolution. The practice has been to include a table, prepared using JCT estimates, showing current-law levels of tax expenditures in the committee report. However, that table is generally not discussed during committee deliberations.

There is no other formal process in place for reviewing or considering tax expenditures as part of the budget process. The budget resolution displays revenues in a single line, with no breakout of the tax expenditures implicitly assumed within the total. This differs from other spending programs where spending levels for each major functional area are supplied within the budget resolution itself, allowing for discussion about priorities. As a result, tax expenditures receive much less scrutiny than other spending programs.