The Response to COVID-19 Requires a Stronger Federal, State, and Local Partnership

Learn More in the Budget Committee's Coronavirus Resource Center

The COVID-19 pandemic is shining a spotlight on the importance of the federal, state, and local partnership. State and local leaders are on the front lines of the public health response: from issuing stay-at-home orders to planning for increased hospital bed capacity, governors and mayors are leading the charge to flatten the curve of new COVID-19 infections. But they cannot do it alone: the federal government has a critical and unique role to play in financing and coordinating the nation's public health and economic response to a virus that spreads quickly across state borders. As local communities grapple with the health and economic consequences of the global pandemic, it is crucial that the federal government be a strong, reliable partner.

State and local governments face a grim budget picture — Some of the crucial, early steps taken to slow the spread of the virus are inevitably slowing local economies, and the economic fallout – at least in the short run – will be enormously challenging for state and local budgets. On average, about half of state revenues come from taxes, mostly from personal income and sales taxes. Recent unemployment data suggest that the country is likely in a recession that may be deeper and wider than previous downturns, which will inevitably take a toll on income tax revenue. Furthermore, many states have delayed their income tax filing deadlines to match the federal government's extension to July 15, which means revenue collection will lag as well.

Sales taxes are down, too: the latest Census data show a seasonally adjusted decline in retail sales of 8.7 percent between February 2020 and March 2020, the largest monthly decline on record. Consumer spending will almost certainly increase as the public health crisis subsides, but it may take months before sales tax revenue reaches pre-pandemic levels.

Further complicating matters is the calendar: most states spend the spring developing revenue projections for fiscal years that generally begin July 1. Any revenue projections from early in the calendar year are likely overly optimistic – in fact, many states are already reporting downward revisions – and projections for the next fiscal year are even more uncertain than usual.

During recessions, states face a one-two punch of declining revenues and increasing demand for services. Enrollment in Medicaid and other programs that help Americans meet their basic needs is countercyclical, meaning it generally rises when the economy is weak and falls when the economy is strong. While it is too early to see the effect of the COVID-19 downturn on enrollment data for these programs, one study estimates Medicaid enrollment could increase by 11 to 23 million over the next several months – meaning billions of dollars in new costs to states.

Taken together, when combined with declining tax revenue, states and localities may soon face budget shortfalls that could exceed the worst on record. Even the most prudent planning by states and localities is unlikely to be enough to respond to a downturn of this magnitude. In fact, state rainy-day funds were at record-high levels after fiscal year 2019, but those reserve balances are likely to cover only a small portion of the need.

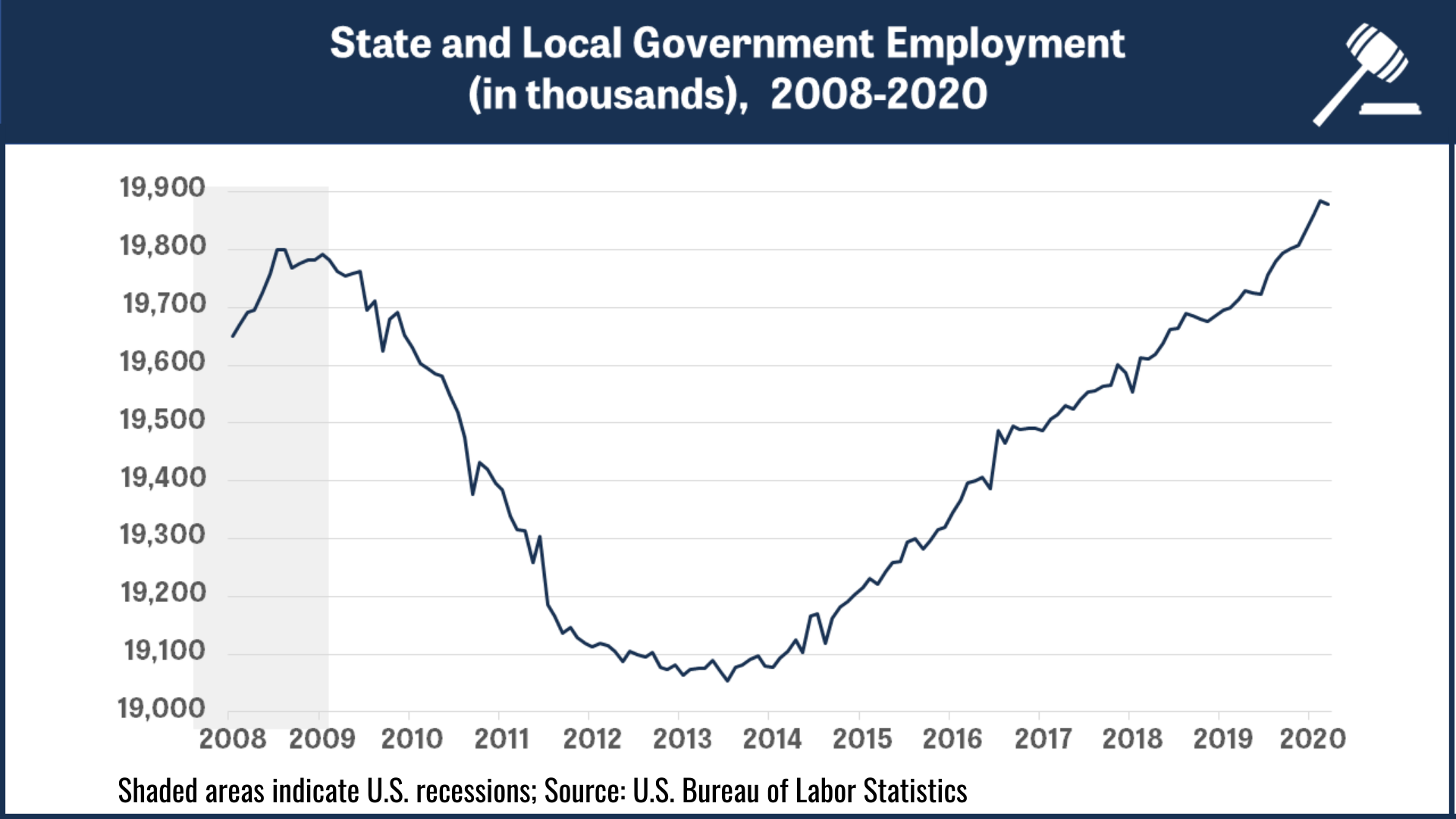

Millions of state and local government jobs are at risk — Because most states are required to balance their budgets, economic downturns can lead to budget strains that force states to cut costs by laying off teachers, police officers, and other government employees – making recessions even more painful, particularly for women and people of color. State and local governments together employ nearly 20 million people – one in every seven American workers – including more than 10 million people employed in the education sector. Experience from the Great Recession suggests that many of those jobs will be at risk as states grapple with budget shortfalls, and it may be many years before they return. Only in late 2019 did state and local government payrolls return to 2009 levels – a full decade later.

State and local governments have already begun announcing layoffs and furloughs due to the COVID-19 downturn, and the pace will likely accelerate in the coming months. Pennsylvania stopped paying nearly 9,000 state employees – more than 10 percent of its workforce. Mayor Eric Garcetti of Los Angeles announced plans to furlough 15,000 city workers. The city of Detroit plans to lay off 200 part-time and seasonal workers and cut pay for 2,200 full-time employees. These are just a few examples, but a recent survey suggests that furloughs and layoffs will be widespread in the coming year. According to the survey, over half of cities with more than 50,000 residents expect to furlough municipal employees as a result of budget pressures related to COVID-19. Among large cities (populations over 500,000), 47 percent expect layoffs.

Vital services that touch the lives of every American may also be on the chopping block — From Main Street improvements to clean water initiatives to infectious disease prevention, state and local governments help ensure the health and well-being of each resident, even if that work often happens behind-the-scenes. State and local governments deliver nearly all public elementary and secondary education, operate libraries, organize police and fire services, and maintain public parks, among dozens of other functions. As states and localities face unprecedented budget shortfalls, funding for these critical services is at risk, and the consequences will be particularly harmful for the most vulnerable Americans who rely on these programs to meet their basic human needs.

For example, Maryland recently froze all non-coronavirus spending, and Governor Larry Hogan signaled that upcoming budget cuts will be severe and probably last for several years. Ohio governor Mike DeWine suggested that an across-the-board cut to the state's budget of up to 20 percent might be necessary. Louisville mayor Greg Fischer warned that the city will be forced to "massively" cut services if it does not receive federal aid, and he announced the furloughs of 380 city employees.

States and localities are economic engines as well as employers and service providers, so deep budget cuts can have macroeconomic implications as well. States and localities spend more than $3 trillion each year on goods, services, and transfers, and have contributed an average of 0.3 percentage points to real annual GDP growth since World War II. But when states and localities cut spending, the effect is reversed: according to one estimate, state budget cuts lowered real GDP growth about 1.2 percentage points between 2009 and 2012.

Federal aid to states and localities is critical, particularly during recessions — While taxes represent the largest chunk of revenue for state budgets, the next largest contributor is the federal government. It varies by state, but on average, the federal government provides nearly one-third (32.4 percent) of all revenue collected by states. This represents about one in every six federal dollars spent each year, or $721 billion in FY 2019. The share of state revenue that comes from federal grants usually rises during recessions, as states receive more federal support from fiscal stimulus packages and automatic stabilizers such as Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and unemployment insurance. Past experience tells us that federal aid to states works: the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 and a later extension closed 24 percent of state budget gaps between 2008 and 2012, primarily through enhanced federal funding for Medicaid and education.

As states and localities respond to one of the most challenging and devastating global public health emergencies in generations, it has never been more important for the federal government to be a strong, reliable partner. Congress passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to provide critical, initial support to state and local governments dealing with budget shortfalls related to COVID-19, but more aid is necessary. The consequences of inaction – layoffs and slashed public services – will result in a deeper and more painful downturn. Abandoning states and localities and leaving vulnerable communities to fend for themselves amid this pandemic is not an option. Support from the federal government is critically important to help flatten the curve of coronavirus infections, heal local economies, and keep our nation moving forward.