Our COVID-19 Response Must Be Dictated By What America Needs, Not Unfounded Fears About Debt

Learn More in the Budget Committee's Coronavirus Resource Center

In the face of COVID-19 and the social distancing measures needed to contain it, Congress has acted swiftly and aggressively to deliver vital public health resources and support for workers, businesses, and families. While the measures taken to date are providing critical relief, much more must be done to safeguard Americans' health and economic security through what may be a prolonged downturn. Fortunately, the United States has ample fiscal space to end the pandemic, mitigate its economic damage, and rebuild a stronger and more equitable economy. Congress must ensure that our fiscal response to the crisis is defined by what our nation needs to fight and recover from COVID-19, rather than an inflexible and misplaced focus on the debt.

We are fighting an unprecedented downturn — In the span of only a few weeks, the unemployment rate has surged from a 50-year low to what may be the highest level since the Great Depression. The unprecedented speed and breadth of the downturn has left millions of families without their livelihoods, necessitating the historic public health investments and emergency economic relief enacted to date. As Federal Reserve Chair Jay Powell said recently, "People are undertaking sacrifices for the common good. We should make them whole. They did not cause this. This is what the great fiscal power of the United States is for, to protect these people from the hardships they are facing."

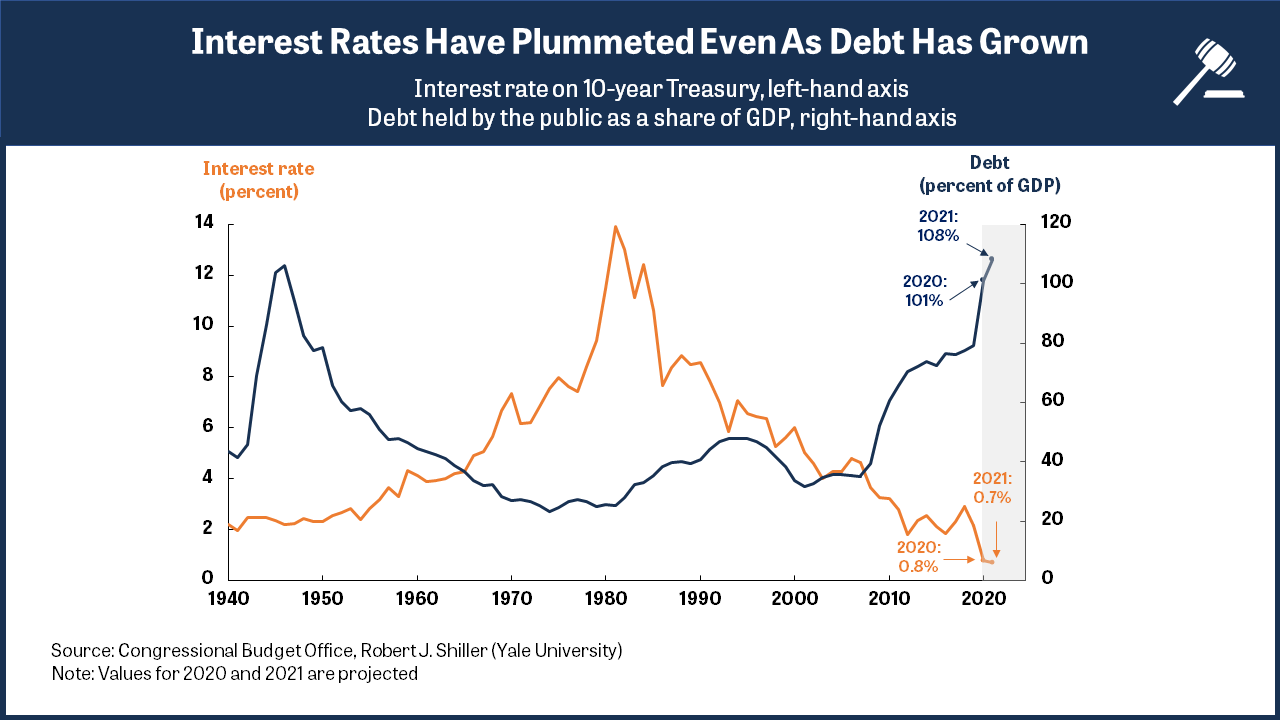

The economic collapse and Congress' efforts so far to counter it will substantially increase deficits over the next several years, driving public debt as a share of the economy to exceed the record levels set in World War II. According to the Congressional Budget Office's (CBO's) preliminary projections, deficits as a share of GDP will rise to 18 percent in fiscal year 2020 and 10 percent in 2021. Debt as a share of GDP would be 101 percent by the end of 2020 – 20 percentage points higher than the pre-pandemic projection – and 108 percent in 2021. While this is a substantial and rapid rise in the debt, these estimates must be understood in the context of our economic environment and the emergency we are facing today.

Indeed, more federal aid will be needed to support families and the economy through the crisis. CBO expects that the economy will contract sharply this year, with only a modest rebound by the end of 2021. Assuming no further action by Congress, real GDP is projected to shrink by 5.6 percent in 2020 – the largest annual decline on record going back to 1948 – with the unemployment rate peaking at 16 percent in the third quarter of the year. By the end of 2021, CBO expects unemployment would still be 9.5 percent, with 6 million fewer people in the labor force than the agency projected in January 2020. The economy would be smaller in real terms at the end of 2021 than it was at the end of 2019.

There is no debt crisis — Although the debt will rise to record heights due to the pandemic, there is currently no evidence that it is endangering the economy, fueling a fiscal crisis, or pushing us against the limits of our fiscal space. Interest rates, which were already near historic lows prior to the pandemic and projected to remain low, have since fallen even further. The United States can now take out a 10-year loan at an interest rate of less than 1 percent – a fraction of the cost it paid to borrow 20 years ago, when the government was running budget surpluses. Adjusted for inflation, the cost of borrowing today is actually negative. Expectations of future inflation, moreover, plummeted in the wake of the pandemic and continue to be muted even after Congress passed each of its relief packages.

That interest rates and inflation remain low suggests that investors have not lost faith in our creditworthiness or our status as the world's safest investment. Nor does the increase in our borrowing appear to be at the expense of private-sector investment, so there is little reason to be concerned that our debt will slow economic growth. Overall, markets today appear to be much more concerned about the economic consequences of a severe recession than of rising federal debt.

While the risks posed by our debt could rise in the future, underlying trends give some reasons to be skeptical. Interest rates and inflation have fallen over the last 30 years even as debt has soared, leading economists to reevaluate the costs of debt. Many of the trends thought to drive these declines, such as demographic change, are unlikely to reverse after the pandemic or anytime soon after that. If anything, COVID-19 may further entrench low interest rates going forward: according to one study, pandemics are associated with substantial declines in interest rates that persist for 40 years. Policymakers must continue to evaluate the risks debt may pose as the economic environment changes, but there is simply no evidence to suggest that a debt crisis is any more likely today than it was before the pandemic.

Low interest rates keep debt service manageable — Crucially, low interest rates help ensure that interest spending remains a relatively small portion of the federal budget. Interest payments as a share of GDP were relatively low by historical standards before the pandemic, and the sharp decline in interest rates since then will further offset some of the cost of new borrowing. CBO projects that interest rates on 10-year Treasury notes will average 0.7 percent through 2021, only one-third of the 2.1 percent average rate in 2019. As a result, CBO estimates that spending on interest this year and next will decline, even with the increase in deficits. According to another forecast, interest payments over the next five years will change little from CBO's pre-pandemic projections and remain well below what we paid in the 1980s and 1990s.

The interest we pay on our debt, rather than the debt itself, is the actual fiscal burden we face each year. Our experience after World War II is instructive: the debt peaked at 106 percent of GDP in 1946 and fell to less than one-third of that within 20 years – but not because we repaid two-thirds of the debt in full. Instead, we paid interest as it came due, while strong economic growth reduced the debt ratio. Not only can we easily meet our interest payments today, their relative affordability suggests we have the fiscal space to fight the recession and invest in our future – both of which will be crucial to spurring growth and keeping our debt sustainable.

Economic aid is preventing an even worse economic and fiscal collapse — Fiscal support is critical for containing the pandemic's damage and forestalling worse economic and budgetary outcomes down the line. According to one preliminary estimate, the CARES Act will soften the decline in GDP in the second quarter of this year and produce 1.5 million new jobs alone by the end of the third quarter. Over the next two years, CARES is estimated to increase GDP by more than $800 billion. While much more must be done, these projections make clear that the relief Congress has provided to date is staving off an even more destructive downturn.

Ensuring that the recession is as short and shallow as possible and that the economy receives the support it needs to achieve a strong recovery are the most effective things policymakers can do to improve our long-term economic and fiscal outlook. As a largebodyof evidence shows, recessions can lead to permanent economic losses and reduced opportunity – scars our economy still bears from the Great Recession. Aggressive fiscal responses that stem the damage and foster growth, however, can actuallylower debt-to-GDP ratios and interest rates, even among countries already carrying high levels of debt. Investing in public health, supporting family incomes, and keeping businesses afloat through this crisis will limit losses to employment, output, and revenues. As the risk to public health recedes, fiscal stimulus and pro-growth investments will be critical for supporting a rapid and durable recovery.

Accordingly, failure to fight the pandemic and the accompanying economic fallout presents a more severe risk to our economy and our budget than the short-run deficits we must run to fight them. Unfounded fears of the debt, rather than any real economic constraint, hobbledthe response to the Great Recession from the outset, producing a fiscal response that was too small and withdrawn too soon to fully match the depth of the downturn. To emerge from this crisis on strong economic and fiscal footing, Congress must do whatever it takes to end the pandemic, mitigate the economic damage, and ensure a strong recovery.

A brighter economic and fiscal outlook requires investment, not austerity — Like clockwork, some policymakers are pointing to our debt to argue that there is no longer room in the budget to fight this crisis and that our focus must now shift to deficit reduction. They will go on to ignore all of the evidence described above and argue that we are on the verge of a fiscal collapse that can only be avoided by slashing spending on crucial programs and investments. Of course, these are by and large the same policymakers that voted for deficit-busting tax cuts for the wealthy.

We know from experience, however, that austerity is not only cruel but also counterproductive. Congress' abrupt turn to deficit reduction in 2011 – when the unemployment rate was more than 8 percent – shaved more than a percentage point off of economic growth that year and continued to serve as a severe drag on our economy for years after. While many Republicans at the time claimed austerity would be "expansionary," it instead, predictably, led to a historically slow and painfully uneven recovery, undermining our economic and fiscal outlook. Indeed, researchshows that countries' attempts to reduce debt after the Great Recession likely resulted in higher debt-to-GDP ratios due to austerity's long-term negative impact on GDP.

A misguided focus on austerity has also allowed severe deficits in the real economy to grow – a reality the pandemic has magnified. Decades of underinvestment in public health, infrastructure, education, and more have left us less safe, less resilient, and less able to effectively respond to crises, while deep and persistent racialdisparitiesin health and economic security have left people of color more vulnerable to both getting sick and losing their jobs. As these real deficits underscore, our country had enormous needs even before the pandemic.

In the years ahead, our country will need bold public investments that lay the groundwork for a more productive, dynamic, and equitable economy than what we have now. This will mean investing in workers, supporting families, and addressing inequities that undermine our prosperity. There is no cutting our way to economic growth or fiscal sustainability.

Emergency spending is not the source of our fiscal challenge — Over the next several decades, the United States will face a growing gap between spending and revenues driven in part by an aging population and rising health care costs. This structural gap, rather than the temporary spending undertaken to combat the pandemic, is the actual fiscal challenge our country confronts. Congress will need to take steps to gradually reduce this gap, including pro-growth investments and progressive revenue policies. But as CBO Director Phillip Swagel testified earlier this year, our fiscal challenge is long term, "not an emergency."

In the coming months, some policymakers will blindly recite our debt statistics to stoke fear, fight against additional aid for workers and families in need, and justify – without context or evidence – the urgent need for austerity. But we know that we have the resources to carry our nation through this pandemic, support families through the entire length of the economic downturn, and build a more resilient and equitable economy than what we had before. To secure a brighter economic and fiscal future, Congress must ignore efforts – misguided at best and bad-faith at worst – to use the debt as an excuse for inaction and austerity and instead commit to doing whatever is needed to fight the real emergencies confronting us today.